Welcome to this latest edition of From a Climate Correspondent. If you'd like to support us, you can invite us for a coffee over at our Patreon page. We're grateful for any contributions!

A bridge in the Pin Valley in the Himachal Pradesh state. Image credit: Ankit Lal

What started three weeks ago as a relatively minor border squabble between China and India in Ladakh, the country’s highest plateau, has now escalated into a full blown diplomatic crisis. After the death of 20 soldiers in combat, India is now responding with economic measures ranging from high tariffs on imported solar modules to a ban on tens of Chinese apps, including the much loved video platform Tiktok.

But while borders seem to matter so much to some that protecting them is worth countless human lives, this is not the case if we take a step back and look at where we are as a species. In fact, in the grand scheme of things, borders don’t matter at all.

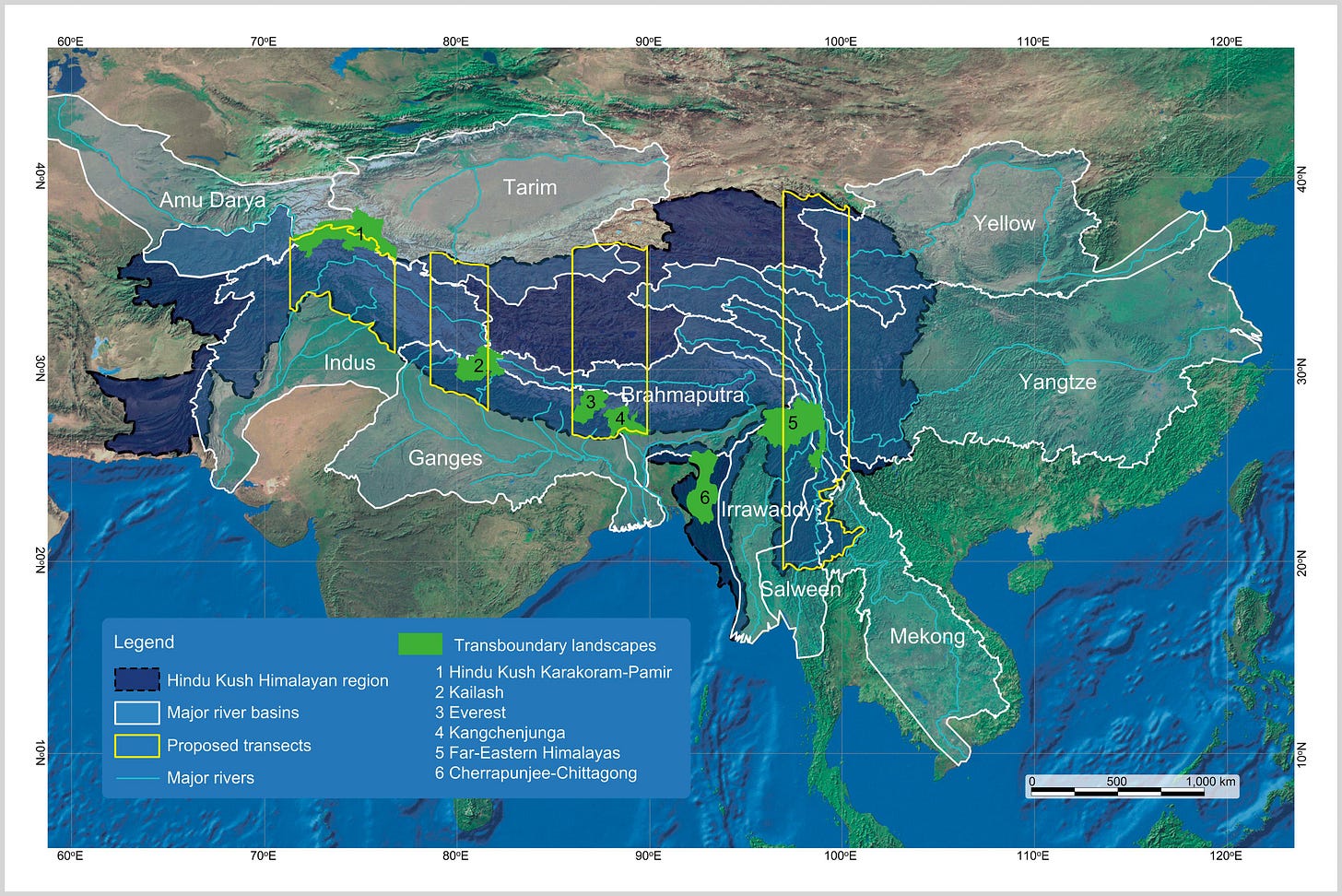

The Himalayas are part of the third-biggest water reserve in the world, the Hindu Kush Himalayan region, which according to the most comprehensive scientific assessment of the region is poised to lose one third of its glaciers by the end of the century, even under the most optimistic climate mitigation scenario.

About 1.6 billion people depend on the water stored and released by the Himalayas to drink, irrigate their crops and sustain their livestock. When climate change topples this fragile balance, everyone loses.

But the region is also split between eight countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, India, Myanmar, Nepal, and Pakistan) with conflicting political interests, which often take precedence over the need to take collective action.

A view of the Pin Valley in the Himachal Pradesh state. Image credit: Ankit Lal

In 2017, during the flood season, tensions spiked in the Doklam border area. A few days in, China stopped the supply of real time weather data which would have helped locals prepare for flooding events.

As director of the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), David Molden’s mission is to make sure that cooperation in the Hindu Kush Himalayan region remains strong, in order to protect both the environment and the livelihoods of the mountain communities. From the point of view of a multinational team that has been working for many years in the region, the current political situation feels bizarre, he says. “All of us are very good friends.”

However, he recognises that “we are working in a very sensitive political area, and there are issues that [within our work] we can’t touch.” For example, scientists never weigh in on border disputes or who gets what share of water, but there is far more cooperation on how to prevent disasters from drought and floods, he says.

Scientists at ICIMOD are focusing on both political and technical issues to stave off the many risks the region faces. Their goals include shared monitoring infrastructure and the development of an integrated system for the management of water resources . They are also at work to help build a regional cryosphere knowledge hub to collate and share information on snow, glaciers, permafrost and glacial hazards. In turn these tools would help develop climate resilience and support disaster risk preparedness in the region.

A map of the Hindu Kush Himalayan region - Image credit: ICIMOD

But while countries are currently cooperating, the mounting tensions mean it’s not inconceivable that China or India may drop out of one or more research programs.

The area is also prone to wildlife trade, Molden says. “Countries are taking steps to slow down the problem, especially after Covid-19 highlighted the associated risks, so we don't want to see that opportunity vanish.” The costs of non cooperation, he says, “are way too high.”

We are living in perilous times, and while few in India may be paying attention to the fate of the Himalayan glaciers right now, failing to protect them will have a more brutal and longer lasting impact than any ban on phone apps or racist campaign against Chinese nationals in India.

I wonder if, after braving the mountains for twenty years and witnessing their resilience, Molden has become an optimist. He tells me that as long as scientific cooperation continues, trust can be restored: “In spite of the tensions of the day, these platforms always provide a place to talk.”

Must reads from the region

Borders don’t matter (in the age of climate change), Vivek Menzes, Dhaka Tribune

This poetic op-ed on the main Bangladeshi newspaper reminds us what we stand to lose when we focus on the wrong enemy.

Bihar floods: An annual blame game between India and Nepal, Rohin Kumar and Saket Anand, Gaon Connection

This compelling reportage, from India’s only news platform dedicated to rural life, captures the reality of shared water management and why it matters: one mistake upstream, countless people can be affected further down.

Glacier studies in Ladakh, Himachal Pradesh flag stark climate change impact, Jayashree Nandi, Hindustan Times

A new study assesses the state of the glaciers in the western Himalayan region, detailing the extent of the ice loss we can expect in the coming decades. While the glaciers will certainly not disappear, the change is likely to have a profound impact on water availability for local communities - another vulnerability calling for better manage of the mountain’s resources.

India's first ever climate change assessment, Bibek Bhattacharya, LiveMint

India’s first national climate assessment paints a bleak future for the country. In a worst case scenario, the frequency of summer heat waves is likely to be three to four times higher than pre-industrial levels, and their duration is likely to double by the end of the century. Those who have ever lived in India can truly appreciate how dreadful this prospect is.

What else I have been reading

Even the South Pole Is Warming, and Quickly, Scientists Say, Henry Fountain, The New York Times

The South Pole, the most isolated part of the planet, is also one of the most rapidly warming ones, scientists said in a paper published in Nature Climate Change, with surface air temperatures rising since the 1990s at a rate that is three times faster than the global average.

Been forwarded this email?

Did someone send this on to you? Why not sign up yourself!

Who we are

Lou Del Bello is an energy and climate journalist based in Delhi, India.

Jocelyn Timperley is a freelance climate journalist based in San José, Costa Rica.

India Bourke is an environment journalist based in London, UK.

Mat Hope is investigative journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.