Welcome to this latest edition of From a Climate Correspondent. If you'd like to support us, you can invite us for a coffee over at our Patreon page. We're grateful for any contributions!

And if you are not yet a subscriber, you can sign up here:

An apple grower in Himachal Pradesh - Image Credit: Neil Palmer (CIAT)

When thinking of farming in India, most of us would picture green rice paddies stretching into the horizon. India is the second largest rice producer in the world, but there is much more to its fields and orchards than rice and mango.

In fact, India is also the world's fifth largest producer of apples, and the bulk of its production is concentrated in a tiny corner of the Himalayan region, where the climate is just right for the trees to grow strong. Here, in the mountain state of Himachal Pradesh, apples are the main source of income for local farmers.

Trouble on the hills

Enter climate change, and warmer winters are throwing traditional apple farming out of kilter.

“Since 1995, farmers in certain mountainous areas are starting to replace the apple orchards with vegetables, because snowfall has declined there and winter temperatures have gone up,” says Jyoti Singh, a climate researcher at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT) in Delhi. “This means that the quality and quantity of fruit has decreased drastically.” If an apple tree doesn’t get cold enough when it’s dormant in winter, the hormones responsible for the dormancy don’t break down and the flower buds may open too late in spring - or not at all. “If anything happens to the apples in Himachal Pradesh, that would destroy their entire economy.”

With her team at IIT Delhi, she set out to test a daring approach to save the Himalayan apples - solar radiation management. They used a computer model to chart the evolution of local apple species under current climate change trends, and added a corresponding ‘geoengineered’ scenario in which stratospheric aerosols are increased for 50 years from 2020 through 2069. The model simulates a technique that sprays sulphur dioxide into the atmosphere to reflect solar rays away and reduce their warming effect on earth.

The researchers decided to study the apple tree because as a deciduous species, namely one that loses its leaves annually, it is more valuable than other crops, with greater risks of something going wrong.

“Crops such as rice, wheat or maize are seasonal and you harvest two, maybe three times a year,” Singh says. “But when we talk about fruit, we need to establish orchards, which take at least three to five years to start producing fruits.” Saving the orchards means protecting many years of investment for the farmers that look forward to about four decades of production, Singh explains.

For the 50 years they modeled, the scientists observed that as temperatures went down, apple trees thrived. Solar radiation management was working, at least on paper. But once the artificial cooling was switched off, something unexpected happened. Over five years, the presence of aerosols reflecting the sun’s rays declined, and temperatures bounced back, creating even greater heat stress for the trees and the local biodiversity.

In such a scenario, “the rate of temperature change will be higher than what it would have been under a gradual increase in carbon dioxide due to climate change,” Singh explains.

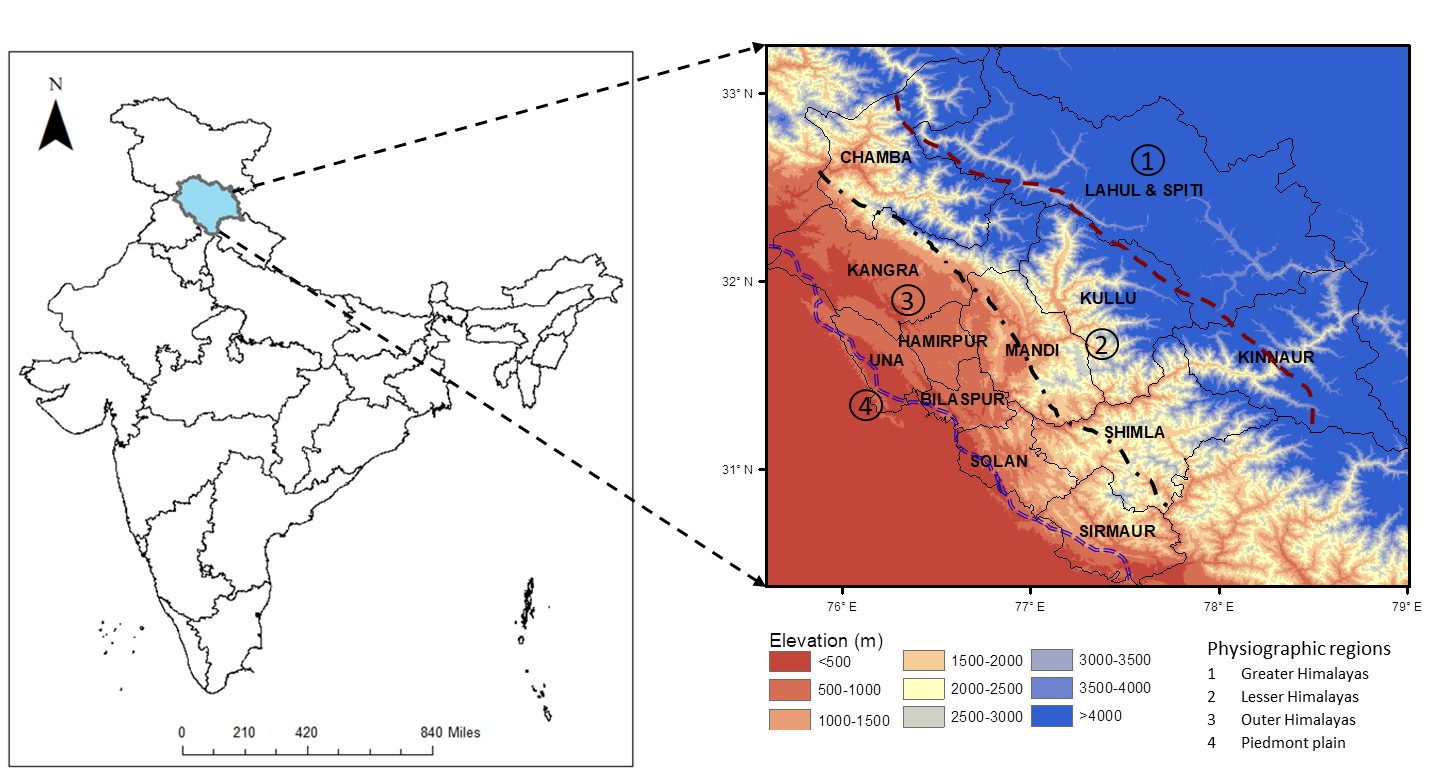

An illustration of the Himachal terrain - Image courtesy of Jyoti Singh, from: DOI http://sci-hub.tw/10.1007/s10584-020-02786-3

Speed of adaptation

Climate change is poised to disrupt mountain agriculture. But farmers can adapt to a slow warming trend, potentially switching crops or diversifying their activities. But when the temperatures change suddenly, Singh says, the chances of failure are much higher.

Geoengineering is controversial, but the general consensus is that certain methods, for example sucking CO2 out of the atmosphere and burying it underground, are vital to mitigate climate change. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) recommends deployment at scale for the best chance of keeping global warming under 1.5C above pre-industrial levels. But none of these high tech solutions is currently well documented.

The Himalayan apples are a cautionary tale for scientists and the public alike: There is no silver bullet to save us from climate change. “Geoengineering can be a good solution,” Singh says, “but before implementing any climate strategy we need to study its impacts on the ecosystems.” Without careful planning, “we may be doing more harm than good.”

Must reads from the region

What the heroin industry can teach us about solar power - Justin Rowlatt, BBC

This is the piece that everyone is talking about this week. It explores how cheap solar has revolutionised opium farming in the most dangerous province in Afghanistan, boosting the heroin market across the world.

Climb or die — Himalayan plants on steep trek to survive climate change - BINJ (original version on The Hindu)

A study from the Botanical Survey of India finds that native plants in the Himalayas are ‘climbing’ the hills in search of cooler environments as temperatures rise.

Rock Dust – a Low-Tech Way to Address Climate Change? - Benjamin Houlton, The Wire Science

Scientists have known for decades that rock weathering – the chemical breakdown of minerals in mountains and soils – removes carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and transforms it into stable minerals. Now emerging science shows that it is possible to accelerate rock weathering rates, slowing global warming and improving soil quality.

Mapping conflict hotspots as leopards adapt to unlikely habitats outside protected areas - Sahana Ghosh, Mongabay India

Rapid deforestation and human-impacts on natural habitats force leopards to venture into unlikely environments outside protected areas for prey and cover, a study finds. The large carnivores have adapted to using human-modified landscapes such as tea gardens, sugarcane fields and farmlands.

What else I’ve been reading

Carbon Border taxes are unjust - Arvind Ravikumar, MIT Technology Review

This opinion piece weighs in on the carbon border adjustment mechanism proposed as part of the EU recovery plan, arguing that it’s hypocritical for developed countries to punish developing countries for carbon emissions while also investing in fossil-fuel extraction there.

Been forwarded this email?

Did someone send this on to you? Why not sign up yourself!

Who we are

Lou Del Bello is an energy and climate journalist based in Delhi, India.

Jocelyn Timperley is a climate journalist based in San José, Costa Rica.

India Bourke is an environment journalist based in London, UK.

Mat Hope is investigative journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.