Welcome to this latest edition of From a Climate Correspondent. If you'd like to support us, check out our Patreon page, or invite us for a coffee over at KOFI page. Thanks for reading!

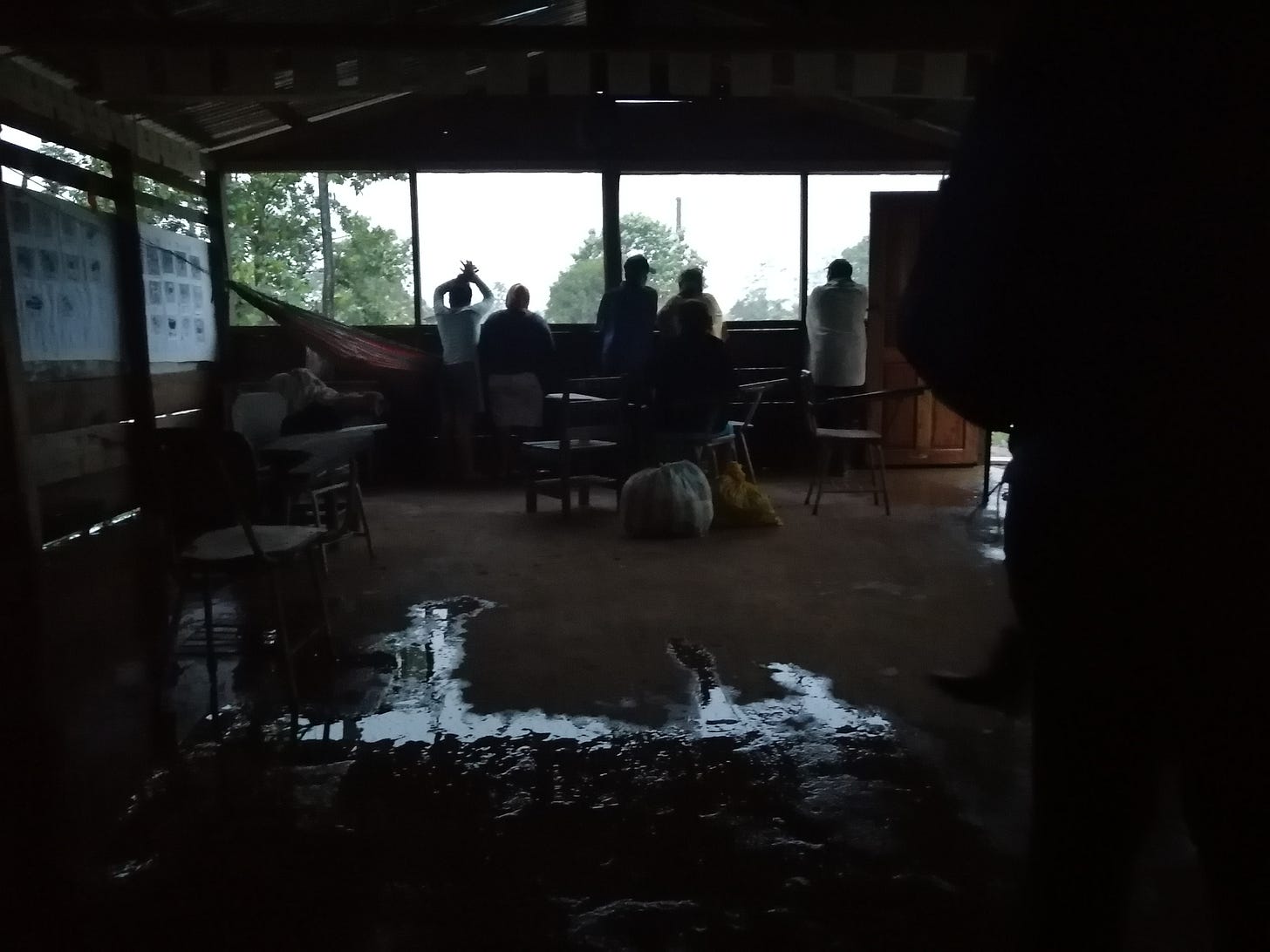

Families in the Wawa Boom community self-evacuated at a community college; government prepared no security plan for the town. Photo by Maynor Salazar.Part 1 of 2

By Maynor Salazar in Bilwi, Nicaragua. Translated from Spanish by Jocelyn Timperley.

The wind blew strong at night and lifted the roof of the house. It lasted twenty seconds, an eternal moment that caused fear among those of us in the shelter. It was twelve o'clock at night; Hurricane Eta had not touched Nicaraguan soil but the damage was starting to be felt all around us. A huge tree fell nearby and blocked the road; several sheets of zinc from nearby houses went flying through the air; the electricity had stopped.

The shelter was located in Nazaret Uno, a community located in Bilwi, in the Northern Caribbean Autonomous Region of Nicaragua. I arrived there just over a week ago, on November 2, together with the photographer Carlos Herrera and a journalistic team from the EFE Spanish press agency, after driving some eleven hours on roads and dirt tracks.

Our aim had been to reach the city of Bilwi to document the ravages of Eta, but we did not manage to get there. The wind was blowing strongly and the night’s darkness reduced the visibility we needed to move easily along the dirt roads under rain heavy enough to shake the truck. Instead, we sought lodging.

We asked for refuge in a Catholic church. They kindly opened the doors of a house adjacent to the temple. There were already six adults and five children in the house. They had come by foot from their home, 30 minutes outside the community’s centre, after deciding to self-evacuate to protect their and their children's lives. The youngest were asleep on a sheet that served as a mattress, while the oldest rested on school desks.

A family taking refuge in the Nazaret Uno community in Bilwi watches the sunrise the first day Eta made landfall in Nicaragua. Photo by Maynor Salazar.We sat at the back, on some benches. With no blankets or food, we decided to stay overnight to get on with work the next day. I thought we were going to sleep, that the rain was going to cause that numbing effect that often occurs when you are in your bed, at home, in the city. This did not happen. That was the first sleepless night, the first time I was facing a phenomenon against which there was no chance of winning.

The hours passed slowly. The adults next to us were shy, they hardly spoke. They had water, little food, and although they were "safe" from the effects of Eta, their faces showed a lot of concern. They did not know what was happening to their homes and all their belongings.

Speed and destruction

Central America is projected to be one of the regions most impacted by weather events linked to climate change, with devastating consequences for its countries. Nicaragua has already seen 0.8-1.3C of warming, depending on the area. More intense hurricanes is one of several expected climate impacts in the country.

A major study published last month concluded that global warming has already increased the chances of storms reaching Category 3 or higher globally; and we already know that rapidly intensifying Atlantic storms like Eta are becoming more common with climate change. Eta was the fifth hurricane on record of Category 4 or higher to have made landfall in Nicaragua.

With Hurricane Eta, everything was speed and destruction: it caused more than 60 deaths in Central America and impacted thousands of people. Constant rains kept El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras and, of course, Nicaragua on red alert. In Nicaragua, two miners died after being buried in a mine due to the soil being destabilised by the rain. Degraded to a tropical storm, Eta moved slowly over Honduras and Guatemala and practically parked in the region, simulating the behavior of Hurricane Mitch in 1998, the second deadliest Atlantic hurricane on record.

“We have been abandoned”

Eta impacted a large part of the territory inhabited by Nicaragua’s main indigenous peoples, Miskitos and Mayagnas. Many live in towns close to companies with several mining concessions, but despite this economic activity it is one of the most impoverished and vulnerable areas of Nicaragua.

It is not only the ravages of Eta which caused destruction in the indigenous communities. Government neglect in many towns deepened the destructive effect of the hurricane.

A house resists the Eta's attacks in the "La 43" community, in Bilwi. Photo by Maynor Salazar.In Wawa Boom, for example, I met Adaluz Ramos, who wanted to show me the precarious situation she, her family, and other neighbours were in. She took me to a hill, at the top of which the largest house in the area with the best structure sat. Many small heads were peeking out of a window. Three were her children, the rest her sister's children, cousins and neighbours, all sheltering in the house to protect themselves from Eta.

It was Tuesday, I had just left Nazareth believing that the situation may be better in other places, but reality hit us in the face. By then the hurricane had struck the city of Bilwi.

There were about fifty people in Ramos’s house. The structure was the strongest in a community full of small wooden houses, even with many of these raised on pillars as protection against flooding. But Ramos told me she was afraid her house would not withstand the 230-kilometer per hour gusts from Eta. She was distraught, but didn’t have a solution at hand.

"We don't know where to go next," she told me with hesitation. Her children and nephews watched one of the zinc sheets that was about to come off the roof. "We have been abandoned," she repeated again and again.

Awaiting the photographer

I spoke with Ramos for almost half an hour, and later published her story in Divergentes, the Central American investigative website I work for. I said goodbye to her and moved on to another community, also in Wawa Boom. Here I met Florencia Salvadora Francis; she was with her family and another fifty people in a shelter at the local school.

No one had brought them there; they themselves had decided to walk to the school from their homes, leaving behind many of their belongings. They were depressed because they had no food, water or medicine. When I greeted Salvadora Francis, she returned the greeting with considerable mistrust. I explained that I was a journalist from the capital who was covering the area. At length she let her guard down, chatted with me. What she said touched me deeply.

In the refuge, food and medicine were scarce due to the uncertainty of Eta's advance into the interior of the coastal territory. "The government did come here with several sacks of food, but they told us that we could not touch them until an official arrived to take photos," Salvadora Francis told me.

She showed me the bags, a concerned expression on her face. In most of these shelters, not only Eta was hitting the population hard. Through its neglect, the government was too.

Maynor Salazar is a Nicaraguan investigative journalist who writes for Divergentes.com. He has written for international media such as Univision, the Connectas platform and various national media. Find him on Twitter @Maynorsalaz.

This post was funded by climate investigation grant awarded to From A Climate Correspondent by the European Federation for Science Journalism (EFSJ) and funded by the BNP Paribas Foundation.

If you’d like to support us to publish more journalism from the front lines of climate change, please consider supporting us with a regular donation on Patreon or inviting us for a one-time coffee over at KOFI. You can also support use by signing up and sharing this article with others!

Must reads from the region

The 2020 Atlantic hurricane season keeps raging with Hurricane Eta, Justine Calma, The Verge

Hurricane Eta ties this season with 2005, writes Calma.

In Nicaragua, supplying beef to the U.S. comes at a high human cost, Nate Halverson, Reveal PBS

The US has turned to foreign beef suppliers such as Nicaragua to fill its meat demand after outbreaks of COVID-19 at domestic meat processing plants. This short film shows how this has actually led Nicaragua to ramp up its meat production, in turn driving indigenous communities off their land.

Is Pinera Impairing Chile’s Leadership on Climate Change?, Francisca Aguayo Armijo, World Politics Review

Latin America is on the verge of realizing its first regional environmental treaty, known as the Escazu Agreement, but Chile is currently missing from the signatory list.

Brazil's Bolsonaro rejects Biden's offer of $20 billion to protect the Amazon, Flora Charner and Ivana Kottasová, CNN

Following the US election result it’s worth remembering this little spat back in September. Biden’s comments which included the threat of “significant economic consequences” for Brazil if it fails to “stop tearing down the forest”.

Can renewables push Latin America towards a green recovery?, Fermín Koop, Diálogo Chino (The Southern Cone)

Hurdles remain as governments still bet on fossil fuels

What else I’m reading

I am in love with football. One of my favourite writers is the Argentine author Eduardo Sacheri. Nobody else has managed to captivate me so much with crime novels that combine perfectly with this sport. I am currently reading “The Life We Thought. Short Stories on Football”, an anthology of football stories involving many characters of special importance in each chapter.

Who we are

From A Climate Correspondent is a weekly newsletter run by four journalists exploring the climate crisis from around the globe. We regularly also feature guest writers.

Lou Del Bello is an energy and climate journalist based in Delhi, India.

Jocelyn Timperley is a climate journalist based in San José, Costa Rica.

India Bourke is an environment journalist based in London, UK.

Mat Hope is investigative journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.

Been forwarded this email?

Did someone send this on to you? Why not sign up yourself!