On 15 April, the Philippines submitted its updated national climate pledge to the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

These pledges, officially called NDCs, capture the national plan and actions of countries to implement the Paris Agreement on climate change. The Philippines, known for being vulnerable to extreme and slow onset weather events, vowed to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 75% by 2030, relative to its business-as-usual (BAU) levels.

The new pledge is a slight increase on the previous 70% reduction against 2030 BAU emissions that the country pledged in 2015. This pledge was already compatible with a lower than 2C world, according to Climate Action Tracker.

Most of the emissions cuts (72%) of the new pledge are conditional, meaning they will only be achieved with the assistance and support of other countries — the big emitters in particular — in the form of climate finance and technology transfer. Just 3% is unconditional, meaning the Philippines will meet this reduction target on its own.

But no matter where the funds come from, it is absolutely essential to ensure the Filipino people and workers are brought along in this transition.

No one should be left behind

Reporting on these UN climate pledges, which were in theory due at the end of 2020, often centres on how ambitious a target is.

This is of course a salient point, considering that countries need to prevent a race-to-the-bottom on emissions in order to avert climate catastrophe.

But while we talk about the numbers, I hope we can talk about the lives behind the target too. By this, I’m referring to the people from the specific sectors and industries where the carbon emissions will be mainly slashed.

These sectors will be agriculture, waste, industry, transport and energy. Looking at these, it’s safe to say the transition to clean energy will have an immense impact on everyone from farmers and coal miners to waste collectors and drivers of public transport. Earning minimum wages, these people are the ones both vulnerable to climate change and the potential job cuts in the transition to clean energy, if done unjustly.

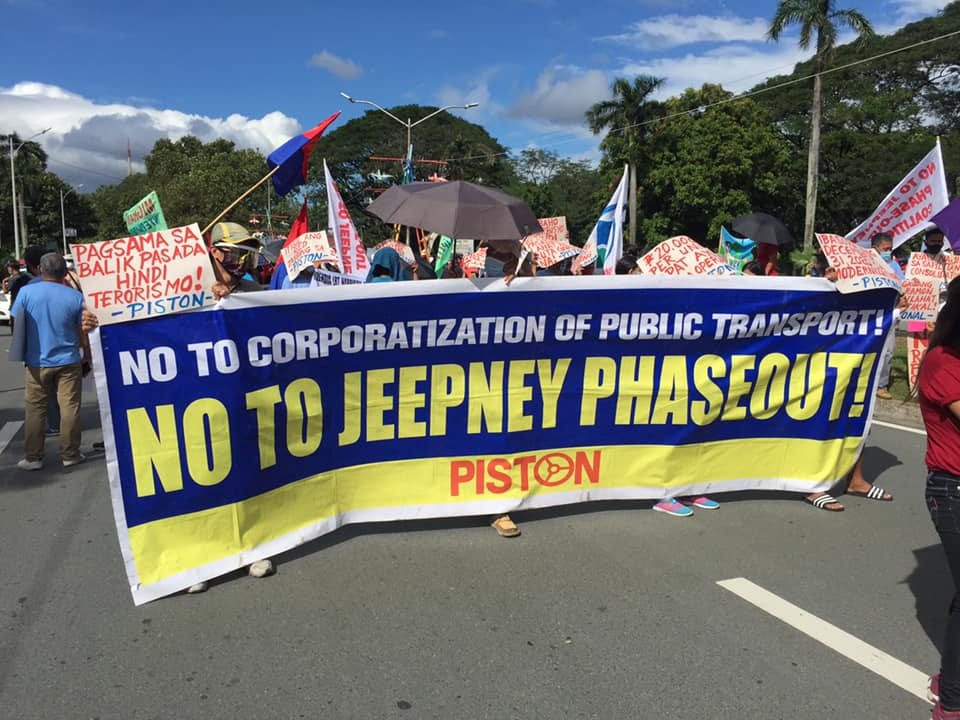

To illustrate what I mean, allow me to go back to the debacle brought by the order in 2017 of Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte to phase out the Filipinos’ main form of public transport, the jeepneys.

Jeepneys are modelled after the American military jeeps, with the vehicle’s bodies painted with colorful designs. They can seat 10-12 people and have been the go-to form of public transport for the everyday Filipino commuter.

Duterte wanted them to be replaced with a modernised version of the same vehicle, those that are Euro-4 compliant or are running on electric engines.

The jeepney drivers, some of whom have been depending on this source of livelihood for 30 years, have been holding transport strikes since February 2017 because Duterte said the replacement of jeepneys that are 15 years and older should be made within two years, by 2020, no ifs or buts. The deadline, however, has not been met with the onslaught of COVID-19, but the order to have them replaced soon stays in place.

Duterte told the protesting jeepney drivers then, in the vernacular - “You're poor? Suffer hardship and hunger, I don't care,” with his usual expletives.

I interviewed these drivers back in 2019, and what’s worth stressing from these conversations was that the drivers told me they don’t oppose the shift to clean energy per se. They know that jeepneys have contributed to pollution and run on dirty fuel, namely gas and diesel.

What they want is to be given the subsidies necessary to switch to cleaner vehicles and the time to do it gradually. After all, we’re talking of hundreds of thousands of jeepney drivers whose families will be affected by an abrupt loss of a source of income.

What the pandemic portends

When the pandemic struck in 2020 and the Philippines was placed under a lockdown, the jeepneys were prohibited from plying the roads. The country’s “king of the road” suddenly was king no more.

Consider this reality when transitioning to clean energy and when thinking of climate impacts. It is a similar story for many other workers who are at the bottom rung of the labour force from these sectors. They must be trained for skills that will make them employable for green jobs.

The transition should be inclusive and just. Make this move more pro-people.

I hope the Philippine government remembers this as the country endeavours to reach its climate target. The numbers should be ambitious, the climate actions humane.

As young leaders from Climate Reality Philippines said in reaction to the NDC target “this mitigation target must be met through a just transition to renewable energy, ensuring that the most affected people will not be left behind.”

If we focus on improving the future for all, in ensuring that workers equitably benefit from a green deal, we will be able to get the support we need from the public so we can reach the NDC target. The people will see that it’s not just about the numbers, but about lives, ultimately.

Must reads from the region:

The lessons of Fukushima: Nuclear power must be regulated, not ditched, The Economist

Looking back at the Fukushima nuclear disaster in 2011, this article makes the case for a better policy architecture for using nuclear power, instead of totally abandoning this option.

For South Korea’s ‘youngest sea women,’ warming seas mean smaller catch , Hyun YoungYi and Josh Smith, Reuters

Warmer waters and ocean desertification have made it more difficult for the haenyeo, or sea women, to gather seafood.

Asia-Pacific, the Gigantic Domino of Climate Change, Vitor Gaspar and Chang Yong Rhee, The IMF Blog

A green deal in Asian economies can do wonders in reducing global emissions.

What else I am reading:

I’m currently trying to finish Bad Science, a book which dispels myths and fantastical claims made by pseudo-science.

Who we are

From A Climate Correspondent is a weekly newsletter exploring the climate crisis from around the globe run by four journalists. We regularly feature guest writers.

Lou Del Bello is an energy and climate journalist based in Delhi, India.

Jocelyn Timperley is a climate journalist based in San José, Costa Rica.

Purple Romerois an climate change and human rights journalist based in Hong Kong.

Mat Hope is investigative journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.