Welcome to this latest edition of From a Climate Correspondent. If you'd like to support us, you can invite us for a coffee over at our Patreon page. We're grateful for any contributions!

Image credit: Zak Derler

Sometimes, worlds collide.

For almost a decade, my day job has required me to keep one eye on a fringe but ever-present group of climate science deniers. In the UK, the legitimate-sounding but intellectually bankrupt Global Warming Policy Foundation (GWPF) has for a decade been at the forefront of an orchestrated campaign to undermine public confidence in climate science. When my job took me further afield, across an ocean or two, I thought there would be respite.

Not so.

Earlier this month, the group published a report called (inevitably and somewhat painfully) Heart of Darkness: Why electricity for Africa is a security issue. The 28-page document, written by a Zimbabwean journalist with no discernable expertise on the issue, takes aim at organisations, like the World Bank, that give international aid and financing to renewable energy projects . Such organisations are, it argues, stymying development on the continent by imposing rules that prevent continued investment in fossil fuels.

When I saw the report, I was transported back to a different time and place. It is full of oft-debunked and archaic arguments about why economic development has to be polluting, and implies that outsiders suggesting it can be driven by clean technologies are “profoundly immoral”.

So far, so very circa-2011. What was new, though, was the response.

Unlike a decade before, when the climate and energy debate was ripe for the GWPF’s misinformation interventions, energy experts on the continent were not going to take the group’s falsehoods at face value.

Expert backlash

“International climate deniers cannot pretend to know Africa better than its people. We have local African experts who appreciate the situation we are in as a result of climate change. We will not listen to anything deniers say,” Amos Wemanya, a campaigner at Greenpeace Africa, told my DeSmog colleagues Zak Derler and Maina Waruru, who broke the story.

“Africa does not need advice from the so-called experts, like Lawson, on how to make its people access energy,” Wemanya added, referencing GWPF founder Nigel Lawson, a former UK chancellor of the exchequer under Margaret Thatcher, and notorious climate science denier.

Eddy Njoroge, a Kenyan entrepreneur and member of the investment committee at the African Renewable Energy Fund (AREF) called the report's claims “misleading and untrue”. “Fossil fuels will not help Africa,” he said, pointing to the continent’s great potential for solar, wind, and hydro-power: “Renewables are better priced, cheaper, and quicker to install, and thus they are far more scalable than fossil fuels.”

Mohamed Adow, founding director of Nairobi-based thinktank Power Shift Africa (and a DeSmog board member) also emphasised this misunderstanding of the continent’s renewable energy potential:

“Africa is blessed with renewable energy and does not need fossil fuels to help people access energy and create growth,” he said. “The cost of renewables has come down significantly and is much lower than that of fossil fuels. So we Africans need to ignore such voices and increase investment in clean energy.”

A continent ahead

That none of these experts’ responses are seen as particularly outlandish shows just how much the context in 2020 has changed since I was writing wordy, complicated, and (I don’t mind admitting) rather boring fact-checks from a mildly grotty central London office in the early 2010s.

That their responses also weren’t particularly hard to solicit is also a sign that those on the continent are well-aware Africa doesn’t have to get to clean development via dirty energy projects, regardless of what those with vested interests in polluting industries say.

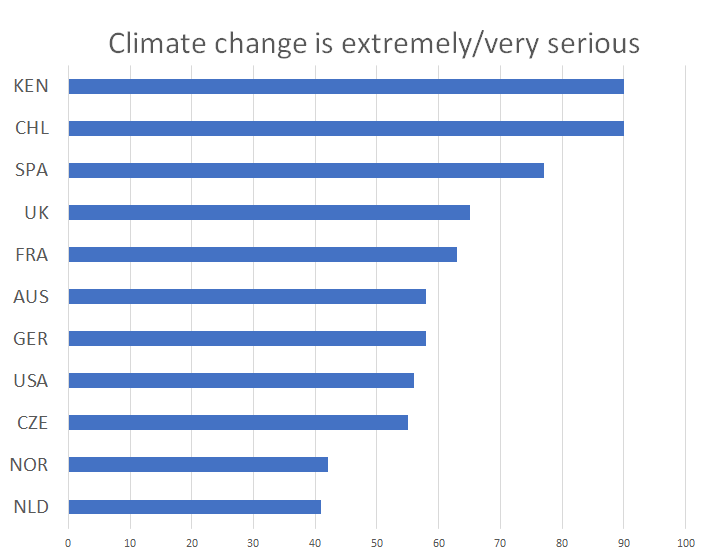

In a recent survey by Oxford University’s Reuters Institute, Kenya came joint top of the countries they surveyed for public concern about climate change, with around 90% saying it was ‘very’ or ‘extremely’ serious.

Source: Selected data from Reuters Institute Digital News Report 2020

That contrasts significantly with countries where climate and clean energy policy is more established.

In the UK (where the GWPF is based), only about 65% of respondents think climate change is very or extremely serious. In the US, where there remains an influential and well-established climate science denial disinformation network, that figure drops to 56%. The Netherlands and Norway fare worst, with only around 40% of people being particularly worried about climate change.

Could it be that those in Africa, the continent most threatened by the impacts of climate change and with the greatest potential to follow a clean development path, can’t be fooled by a Zimbabwean journalist and his coal-backed sources, or a Finnish epidemiologist, or a hereditary peer with a coal mine on his family’s estate, or any other number of ‘experts’ rolled out by groups such as the GWPF to spread disinformation on climate change?

While climate science deniers may be keen to export their misinformation to Africa, the continent seems rightly reluctant to trade.

Must reads from the region

Africa can become a renewable energy superpower – if climate deniers are kept at bay, Mohamed Adow, Guardian

Picking up from DeSmog’s reporting, Director of thinktank Power Shift Africa, Mohamed Adow, offers his perspective “as an African from a pastoralist community in northern Kenya”. “I have seen the suffering that coal-fuelled climate breakdown has wrought on my people,” he says, crediting policymakers on the continent with being “smart enough to know that putting more coal on the fire is not the solution.”

Why Africa’s heatwaves are a forgotten impact of climate change, Friederike Otto and Luke Harrington, Carbon Brief

Two Oxford University researchers outline how in Africa heatwaves will become hotter and more dangerous. That will happen even if global warming is kept below the Paris Agreement’s more ambitious goal of limiting warming to 1.5C. They concluded that, combined with population changes, 20-50 times as many people could be exposed to dangerous heat in African cities by the end of the century.

The road to a just recovery for South Africa: No going back to normal, Ahmed Mokgopo, Daily Maverick

350.org’s Africa campaigner argues that South AFrica’s finance minister has so far “failed to lay out a path for a more just and equal society” in the country’s recovery plans. A post-COVID recovery package must be “focused on wellbeing, where an appropriate Covid-19 stimulus prioritises communities over corporate profits”, he argues.

Close energy poverty gap by empowering women with clean energy, ESI Africa

In an interview, Ifeoma N. Malo, a former senior advisor to the Minister of Power in Nigeria the founder of startup Clean Tech Hub Nigeria, outlines how her organisation is helping women-owned and women-led businesses to close the energy poverty gap by empowering them with clean energy products. “Renewable energy is the new oil and gas”, she argues.

What else I have been reading

Nile dam dispute: Ethiopia, Egypt and Sudan agree to resume talks, BBC

Clean energy comes at a cost, which way exceeds the £3 billion needed to build the physical dam that has been stirring up controversy since 2011. As the three countries of the Nile river basin come together in an attempt to solve the dispute over shared waters, this piece, which comes with a short documentary, gets you up to speed with the issue.

Who we are

Lou Del Bello is an energy and climate journalist based in Delhi, India.

Jocelyn Timperley is a climate journalist based in San José, Costa Rica.

India Bourke is an environment journalist based in London, UK.

Mat Hope is investigative journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.