Welcome to this latest edition of From a Climate Correspondent. If you'd like to support us, you can invite us for a coffee over at our Patreon page. We're grateful for any contributions!

Image credit: Edmar Almeida de Oliveira

“Sustainability” has become such a buzzword that some claim it is losing all meaning.

But while the jargon and marketing around sustainability tends to come from the Global North, the actual sustainable practices have been around long before many of these countries even existed in their current form.

For centuries, many viewed the Amazon rainforest as pristine and sparsely populated, largely untouched by people before Europeans arrived in the Americas. More and more research is showing how inaccurate this view really was.

“We know now that all Amazonia was touched by the hand of man and woman, because the population was huge at that time,” Ben Hur Marimon Junior, a professor of forest ecology at the State University of Mato Grosso in Brazil, tells me by phone one recent evening.

What’s more, there is an increasing recognition that the people living in the forest had a long history of sustainable management practices - many of which we may still be able to learn from today.

Marimon Junior is a co-author of a new paper from Brazilian and British researchers that looks at the carbon and biodiversity benefits of “dark earth” - one major influence of indigenous peoples on the Amazon from thousands of years ago.

Dark earth, also known as black soil or terra preta, is a dark, fertile soil produced by humans by adding charcoal from fire remains and food waste into it. Along with geoglyphs - large geometrical shapes dug into the ground - they are helping to provide the evidence of where and how people lived in the Amazon pre-Columbus.

Carbon win

Tupi and other indigenous peoples of the Amazon are known to have used dark earth to improve soil fertility, farming a system of agroforestry that included trees scattered in the landscape as well as cucumber, pumpkins, a range of varieties of maize and many other different plants. Thousands of these dark earth areas - which are each around the size of a field - are scattered through the Amazon today.

What this new research shows is that these areas have an ongoing impact on the vegetarian, biodiversity, carbon content and tree sizes of the Amazon today.

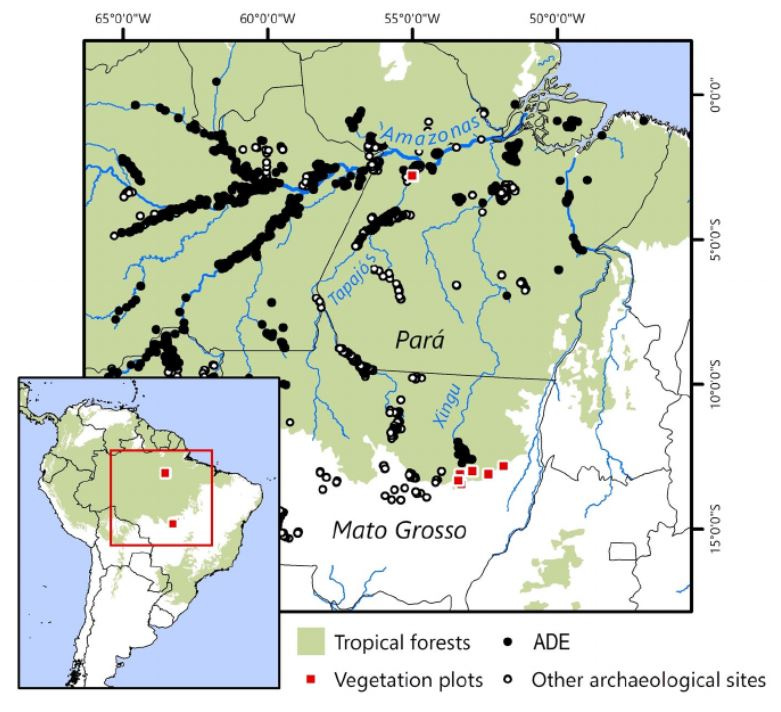

The researchers collected soil samples and identified and counted plant species present in dark earth patches and patches of surrounding forest in the eastern and southern Amazonia.

They found that dark earth areas continue to have a set of species that differ from the surrounding landscape, contributing to a more diverse ecosystem, including with more edible fruit trees, such as taperebá and jatobá.

Plot locations in forests tested by the researchers in southern Amazonia (Mato Grosso state) and eastern Amazonia (Pará state) in Brazil. Almeida de Oliveira et al (2020)

But the research has also found that this vegetation, and the soil below it, is far higher carbon than the surrounding forest. “We know these patches influence a lot in the carbon stock because the biomass is two or three times more than surrounding forests, and in the soil is around eight to ten or more times carbon stocks,” says Marimon Junior.

The dark earth found in the Amazon has around 100 times more pyrogenic carbon than a normal situation, adds Marimon Junior. However, researchers have not yet been able to establish its total stock in all the Amazon. In fact, pyrogenic carbon stocks and dynamics are not considered in global carbon cycle models, leading to systematic errors in carbon accounting, according to a paper published last year in Nature Geoscience.

Another study published last month by a Brazilian/Finnish team of researchers shows similar evidence of domesticated plants by indigenous people in the Southwestern Amazonia. The study finds that both wild and domesticated palm fruits, Brazil nuts and other species were being harvested and eaten here in the first millennium AD.

“Our studies in Brazilian Acre have shown that this part of Amazonia was quite densely populated two thousand years ago,” says Martti Pärssinen, professor at the University of Helsinki and lead author of the paper. “Hundreds of ceremonial earthworks with the system of roads were built. Nevertheless, unlike today, the tropical forest was not converted to the savannah or to monoculture farming fields.”

“At the same time some important trees were also domesticated that affected permanently the structure of the tropical forest. It is not pristine any more.”

These indigenous dark earth and agroforestry practises are not just historical - they are used for food crops today. “The more recent indigenous populations in our region are still making this black earth, because it's a traditional indigenous practice of agriculture,” says Marimon Junior.

However, most are still hidden in the forest - many in areas under threat due to illegal deforestation and fire.

Lessons learned

Marimon Junior tells me there are several lessons other countries and peoples can take on board from this way of managing the land.

Firstly, the practice of adapting only small patches for agriculture while keeping the surrounding forest intact. “We have legislation in Amazonia to keep 80% of the forest intact,” says Marimon Junior. “It's totally enough to make some similar practice of the indigenous people, because we can have small farms, small crops for example, and keep at the same time the very large extensions of forest.”

Areas of land that were once planted can also be abandoned again, allowing the surrounding forest to regrow in them, he adds, leaving patches of increased biodiversity.

Charcoal from a forest fire in the Amazon. Image credit: Ben Hur Marimon Junior

The dark earth patches also increase the fertility of soils without the need for stacks of chemical fertilisers. “Pyrogenic carbon is a soil regulator of chemicals and water at the same time,” says Marimon Junior, noting that modern agriculture could also add pyrogenic carbon from wastes from the rice, sugarcane and other industries. “The indigenous people were able to have a big harvest for hundreds of years cultivating in this land, with a totally natural management.”

And the mixed agroforestry system also allows farmers to harvest a productive crop with no pesticides while preventing the spread of insects, fungi and plant diseases, says Marimon Junior.

It is commonly accepted in the academic community that the pre-Columbian population in the Amazon varied between 5 and 10 million people, maybe more, says Marimon Junior - a population the size of London or even higher living.

“Imagine a lot of people moving from one side to another in all Amazonia, touching the Amazon forest,” says Marimon Junior. “But the management is the difference. They weren't so aggressive.”

Must reads from the region

Pandemic Plunges Puerto Rico Into Yet Another Dire Emergency, Alejandra Rosa and Frances Robles, New York Times Puerto Rico has had some 8,700 confirmed and likely cases of the virus and 157 deaths. But because of a severe drought, its governor has announced parts of the island will have running water only every other day for the foreseeable future.

‘On the edge’: Endangered forest cleared for marijuana in Paraguay, Aldo Benítez, Mongabay Clearing for illicit marijuana cultivation is also taking a toll on the eastern Paraguay’s forests, writes Benítez.

Costa Rica’s Covid-19 response scapegoats Nicaraguan migrants, María Jesús Mora Nacla Nicaraguan migrants are facing discrimination after a spike in Covid-19 infections among workers at agricultural facilities near the northern border, writes Jesús Mora

Brazilian meatpacker expands with World Bank funding but fails to reduce impacts in the Amazon, Naira Hofmeister, Mongabay A $85m grant from the World Bank’s private sector arm to Brazilian meatpacker Minerva seven years ago was granted on the condition that an environmental and social action plan be implemented - but these have not kept pace.

What else I’m reading

One River, by Wade Davis.

I’ve just begun this book by Colombian-Canadian ethnobotanists Wade David which describes the lives and cultures of several indigenous communities he and his colleagues visited in the Amazons from the 40s-70s.

Carbon markets expert Felippe de Leon, who recommended it to me, says what really grabbed him about it was the very clear demonstration of what is meant by indigenous wisdom or similar terms. “I think these get thrown on the ground a lot in our kind of spaces, and even for a lot of people who respect indigenous populations with some sort of reverence, it’s not necessarily obvious how deep that knowledge is and how much it covers stuff that we don’t seem to understand,” he tells me. “How much it is a fully functioning world view and system of knowledge.”

Been forwarded this email?

Did someone send this on to you? Why not sign up yourself!

Who we are

Lou Del Bello is an energy and climate journalist based in Delhi, India.

Jocelyn Timperley is a climate journalist based in San José, Costa Rica.

India Bourke is an environment journalist based in London, UK.

Mat Hope is investigative journalist based in Nairobi, Kenya.